Friday, November 7, 2025

Author: Biketi Charity S. Nelima

Category: Health Insurance

⏱️ Estimated Read Time: 10 min read

Healthcare is not just a social cornerstone, but also an economic driver. According to the World Bank (2025) report, Investing in Health Is Key to Job Creation and Economic Growth. A nation’s productivity depends on its citizens’ health; without access to affordable medical services, labour capacity, innovation and economic output suffer. When people are healthy, they can work efficiently, learn effectively, and contribute meaningfully to economic growth. Poor health, on the other hand, weakens the labour force through absenteeism, low energy, and reduced performance. It also discourages investment in human capital as families spend more on treatment than education or business ventures. Innovation slows down because ill health limits creativity and focus. In the long run, this leads to stagnation in both productivity and income levels.

Additionally, the constitution of Kenya, article 43 guarantee everyone the right to the highest attainable standard of health. The government holds the responsibility of enacting legislative and policy measures that progressively realize the right to health. The Government of Kenya implemented National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) in 1966. As of 2021, NHIF covered 16% of Kenyans despite it being the main coverage in the country. Other private insurers collectively covered just 1% of the Kenyan population, National Library of Medicine, 2020. In 2023 November, NHIF was replaced by the Social Health Authority (SHA), designed to provide healthcare services and ensure that all residents in Kenya can access a comprehensive range of quality health services they need without financial strain.

African Health Business (2021) reveals that out of Kenya’s estimated population of 52.4 million, only 25% have health insurance coverage, inclusive of both public and private schemes, clearly indicating that Kenya is straining when it comes to insurance uptake. Similarly, a report by Cytonn Investments (2023) indicates that Kenya’s insurance sector is growing slowly compared to other key economies, with insurance penetration at just 2.3% at the end of the 2023 financial year (FY). Insurance uptake is still perceived a luxury, particularly among those opting for private insurance, and is often sought only when necessary or as a regulatory requirement for public insurance, where individuals are compelled to register to access public jobs. Consequently, registrations tend to outnumber active contributions.

Figure 1: Insurance Penetration Rate in Kenya.

Source: Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) review.

According to Citizen Digital, September 16, 2025, reported that 26 million Kenyans have registered with the SHA. Of these, approximately 890,000 are contributors from the informal sector, while about 3.1 million are salaried contributors from the formal sector, meaning a total of around 4 million Kenyans are actively paying into the contributory fund. Kenya’s healthcare landscape underwent a major shift in 2023, when the NHIF was replaced by the SHA under the Social Health Insurance Act, 2023. The change introduced new contribution structures, as shown in Table 1, however, prices and contribution amounts remain sensitive factors, particularly for households living in poverty. According to the Ministry of Health 2023, the SHA scheme remains unaffordable for many Kenyans in extreme poverty, despite the government’s efforts to make health insurance more inclusive.

One of the key differences between the two systems lies in enrolment and contribution patterns. While the NHIF had mandatory enrolment for formal sector workers and voluntary participation for informal workers, the SHA now requires mandatory coverage for all Kenyan residents and their dependents. Despite SHA’s impressive registration figures about 27 million Kenyans registered compared to NHIF’s 16.2 million, the number of active contributors tells a different story. NHIF recorded around 7.1 million contributors, while SHA currently has only about 3.5 million. As noted by Citizen Explainer (September 16, 2025), the surge in SHA registrations has largely been driven by government campaigns and the deployment of Community Health Promoters (CHPs) across the country.

Table 1: Comparison of the NHIF and SHIF contributions for different monthly income bands.

| Income Band | NHIF Contributions | SHIF contributions |

| Unemployed | Voluntary Ksh 500 contribution | 2.75% of annual income as determined by the means testing system |

| 0 - 5,999 | 150.0 | 300.0 |

| 6,000 - 7,999 | 300.0 | 300.0 |

| 8,000 - 11,999 | 400.0 | 330.0 |

| 12,000 - 14,999 | 500.0 | 330.0 - 413.0 |

| 15,000 - 19,999 | 600.0 | 413.0 - 550.0 |

| 20,000 - 24,999 | 750.0 | 550.0 - 688.0 |

| 25,000 - 29,999 | 850.0 | 688.0 - 825.0 |

| 30,000 - 34,999 | 900.0 | 825.0 - 963.0 |

| 35,000 - 39,999 | 950.0 | 963.0 - 1,100.0 |

| 40,000 - 44,999 | 1000.0 | 1,100.0 - 1,238.0 |

| 45,000 - 49,999 | 1,100.0 | 1,238.0 - 1,375.0 |

| 50,000 - 59,999 | 1,200.0 | 1,375.0 - 1,650.0 |

| 60,000 - 69,999 | 1,300.0 | 1,650.0 - 1,925.0 |

| 70,000 - 79,999 | 1,400.0 | 1,925.0 - 2,200.0 |

| 80,000 - 89,999 | 1,500.0 | 2,200.0 - 2,475.0 |

| 90,000 - 99,999 | 1,600.0 | 2,475.0 - 2,750.0 |

| 100,000 | 1,700.0 | 2,750.0 |

| 200,000 | 1,700.0 | 5,500.0 |

| 500,000 | 1,700.0 | 13,750.0 |

| 1,000,000 | 1,700.0 | 27,500.0 |

Source: Cytonn Investments (2023)

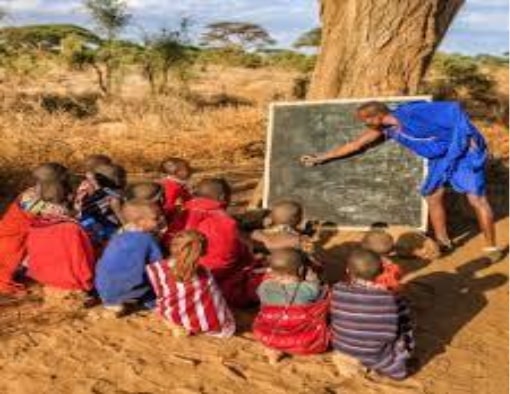

The rural–urban divide continues to undermine equity in healthcare access. Insurance services and quality healthcare facilities remain heavily concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural communities underserved and marginalized, the 2022 update of the health equity and financial protection indicators database. Quality of health Insurance also plays a major role in insurance uptake. When health insurance schemes offer poor-quality services, citizens are discouraged from enrolling or making consistent contributions. People often choose based on the value and experience they receive; many therefore opt for private or individual insurance plans despite their higher cost, as these tend to provide better service and greater perceived benefits.

Private health insurers in Kenya collectively cover just about 1% of the population, a striking figure that highlights how inaccessible private healthcare remains for most citizens. For many Kenyans, private insurance is a luxury reserved for the upper social class, leaving lower-income households heavily dependent on public facilities or out-of-pocket spending. Yet, even for those who can afford it, private coverage is far from perfect. Rising healthcare costs and economic shocks continue to strain both insurers and policyholders, exposing the fragility of a system built more for exclusivity than inclusivity. The result is a widening gap in access to quality care, reminding us that the conversation around healthcare reform must extend beyond public insurance to address the deep inequalities in private health coverage as well. Following the insurers’ protest in July 2025, Business daily Africa revealed that The Nairobi Hospital had adjusted several service charges upward by as much as 61 percent. The revision affected a range of diagnostic and inpatient services, placing greater pressure on both insured and out-of-pocket patients.

The increase in medical charges sparked an immediate reaction from both insurers and consumers. Several insurance providers suspended coverage for The Nairobi Hospital, citing unsustainable cost implications. Consequently, the hospital witnessed a notable decline in patient visits, as many in-patients opted to transfer to more affordable facilities. This situation underscored the fragility of Kenya’s private health insurance sector, where price sensitivity remains high despite being perceived as a service for the financially secure.

The increased price of care suppresses demand; health economics demonstrates that higher costs lead to decreased utilization, even essential services. Despite all this, insurance is still relevant. With insurance, healthcare is guaranteed, resulting in increased economic growth.

Health insurance is more than a financial instrument; it is a cornerstone of individual security, societal stability, and national economic growth. From an economic perspective, it protects households from catastrophic medical expenses that could erase years of savings. In Kenya, the World Bank (2022) estimates that 24.21% of total health expenditure is paid directly out-of-pocket, meaning many families are just one medical emergency away from financial ruin.

Socially, insurance fosters timely and equitable access to healthcare. Studies published in BioMed Central (BMC) Health Services Research indicate that insured individuals are significantly more likely to seek early treatment, which reduces the risk of complications and the need for costly emergency interventions. This not only improves survival rates but also helps build public trust in the healthcare system.

On a systemic level, a healthier population enhances workforce productivity and reduces absenteeism. According to the Social Health Protection Network Study (P4H), improved health outcomes can increase national productivity due to fewer sick days and extended working years. Countries with higher insurance coverage often enjoy stronger economic resilience because healthier citizens are better able to contribute consistently to economic activities.

Kenya’s health insurance system stands at a crossroads between ambitious reform and harsh realities of coverage and affordability. Health is not only a constitutional right but also a crucial driver of economic growth and productivity. A healthy population fuels innovation, education, and labour efficiency, yet millions of Kenyans remain uninsured or unable to sustain contributions. Since independence, Kenya has sought to achieve universal health coverage through the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), introduced in 1966. However, by 2021, it reached only 16% of the population. The 2023 reform replaced NHIF with the Social Health Authority (SHA), promising broader inclusion and financial protection for all citizens. Despite registering over 27 million people, active contributions remain low, only about 3.5 to 4 million are consistently paying, compared to NHIF’s 7.1 million. This gap underscores a persistent challenge: widespread registration without sustainable participation.

Several factors hinder progress. Health insurance is still perceived as a luxury, particularly in the private sector, where only 1% of Kenyans are covered. Economic hardship, poor service quality, and rural–urban inequality exacerbates the problem. Rising healthcare costs, further limit access, even for the insured, as insurers suspend coverage and patients shift to cheaper facilities. Insurance remains vital for protecting families from catastrophic medical expenses. With 24% of Kenya’s health spending paid out-of-pocket, one illness can push households into poverty. Socially, insurance improves early treatment and trust in healthcare systems; economically, it enhances productivity and national resilience.

It is commendable to both the government and private insurers for expanding healthcare access through insurance initiatives, which have enabled millions of Kenyans to benefit from reduced treatment costs and more regular medical care. However, For the Government of Kenya to achieve the highest achievable standard of health, several macroeconomic factors must be considered, as they are closely interrelated.

Employment creation, whether through innovation or deliberate job expansion strategies, is essential. Increased employment enables citizens to earn and spend more, thereby facilitating regular contributions to the Social Health Authority (SHA) and strengthening the national health financing framework. The government has proposed a mechanism to assess contributions for unemployed individuals; however, for those in extreme poverty or the informal sector with no consistent income, even the KSh 300 minimum monthly payment (KSh 3,600 annually) can pose a significant financial burden.

The rural–urban divide continues to undermine equity in healthcare access. Insurance services and quality health facilities remain heavily concentrated in urban centres, leaving rural communities underserved and marginalized. World Bank, 2022. To achieve the highest attainable standard of health, the government must prioritize equitable distribution of healthcare resources and strengthen health service delivery across all counties.

Public education and awareness about the new Social Health Authority (SHA) system is equally important. Many Kenyans still associate healthcare coverage with the now-defunct National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), resulting in widespread confusion and misinformation. This lack of awareness has led to instances where patients have been stranded in hospitals or defrauded by fake SHA agents, highlighting the urgent need for better sensitization and transparency. Citizen Digital, 2024.

Payment requirements under SHA often demand full annual contributions upfront for non-salaried members, an additional hurdle for low-income earners. Several reports have highlighted cases where patients were turned away from hospitals or forced to pay out-of-pocket due to system failures or registration challenges during the transition from NHIF to SHA, exacerbating financial strain.