Monday, October 6, 2025

Author: Beth Wangari Ng'ang'a

Category: Public Finance

⏱️ Estimated Read Time: 8 min read

Strained public financial resources leave minimal budgetary allocations for development expenditure. In the 2025/26 Financial Year Budget Statement, only Kshs. 693.2B, 3.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was allocated for development expenditure. Additionally, the budget statement stipulated that the fiscal deficit for the financial year would be financed through domestic and external borrowing, currently totalling Ksh. 923.2 billion, equivalent to 4.8% of GDP. Given the underlying public debt constraints, the government should pursue other sustainable and alternative financing options that deliver projects with a positive social impact and minimise public costs. An alternative funding mechanism would be Social Impact Bonds (SIBs), which will be discussed in this blog.

SIBs: Pay for Success Bonds Contextualised.

Robert Cohen’s thesis that businesses should not only focus on making profits but also bring positive societal value gave rise to SIBs. A Social Impact Bond is a performance-based or success-based contractual arrangement whereby private investors invest capital to finance a social intervention, and the government repays the investors when and if the agreed social outcome is achieved. As such, once a social need, e.g. unemployment, is identified following a government’s feasibility study, the SIB deal is structured in terms of raising capital from the investors, determining the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and procuring the service providers. After that, the SIB project is implemented, evaluated against the KPIs then the government pays the investors if they have been met.

An SIB must possess the following elements: one or more specific, meaningful and measurable social outcomes that align with the government’s agenda, e.g. Inclusive education for children living with disabilities, definite project timelines and KPIs for achieving the social outcome and favourable legal conditions to support the achievement of the social outcome.

a) Investors – They include Public Benefit Organisations (PBOs), banks, pension funds, institutional investors or individuals that supply capital to the SIB intermediary for a particular project.

b) SIB intermediary – This is a special purpose vehicle that coordinates the raising of revenues, determines the transactional details, monitors and evaluates the social outcome and manages the payment process to the investors. In other words, the intermediary coordinates the whole SIB process from inception to completion.

c) Outcome funder – Determines the payout terms at the beginning of the project and pays the investors when the intended intervention is achieved.

d) Service providers – They deliver the social services to the public needed to achieve the social intervention.

e) Evaluators – To consider and validate the results the intervention has achieved for payment purposes.

SIBs in Action.

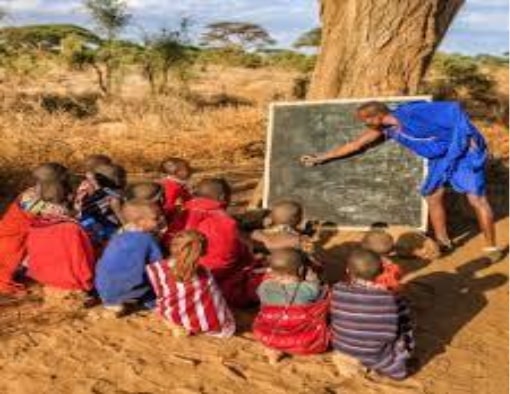

Some countries have exploited SIBs to solve their social problems, such as improving the quality of education, reducing the poverty rates, recidivism and unemployment rates, among others. This section investigates various implemented SIBs from various countries and their success in bringing social development.

UK implemented the Peterborough SIB in 2010 intending to reduce the re-offending rates of inmates who were released from Peterborough prison. In 2007, it was noted that around 60% of the short-term prisoners, that is, those imprisoned for less than a year, were convicted again at least 12 months after their release. As a result, the Gordon Brown government, the outcome funder, worked together with Social Finance, the SIB intermediary, to reduce the re-offending rates. In 2010, Social Finance managed to raise £5 million from investors such as trusts, and they worked with an umbrella of service providers known as One Service. One Service was made up of several organisations such as Ormiston Families, TTG Training, YMCA, MIND, John Laing Training and St. Giles Training that worked together to respond to the prisoners’ needs, such as counselling and skill acquisition. In July 2017, it was announced that this SIB had reduced the short-term offenders’ re-offending rates by 9% against a set target of 7.5%. Consequently, the government paid the investors their initial capital investment with an additional 3% per annum returns for the investment period. This cost was a lesser price to pay, considering the Prison Break report published in 2010 stipulated that crime costs the UK 72 billion Euros per year, with the recidivism costs being 60,000 Euros per prisoner.

In 2018, South Africa had a 40% Youth (15 – 34 years) unemployment rate. Additionally, these youths lacked any formal training. The South African Enterprise and Investment Department launched the workforce SIB in 2018 to equip the youth with the needed skills in the job market and place them in employment. The Bond4Jobs was the intermediary which coordinated the financing and was able to raise US $ 2.42 million with Harambee Academy as the service provider in terms of equipping them with the requisite skills and placing them in employment. Between April – December 2018, 600 youths had already been employed, and therefore, the project was able to achieve its target for the 1st year. The outcome payment was US $ 2.71 million because it was able to achieve its target by ensuring that the youth had the skills required in the job market. This impact was a departure from the Education Ministry’s allocation of US $ 14 billion to post-secondary education annually, yet with low employability rates.

SIBs' Viability in Kenya.

Kenya faces many problems that can be addressed through Social Impact Bonds. These include poverty, unemployment, poor nutrition, high crime rate, poor sanitation, social care, informal settlements and health sector challenges. This situation is contrary to Article 43 of the Constitution, which provides for every person’s economic and social rights, such as the right to quality health care, adequate housing, proper sanitation, to have food of acceptable quality, clean and safe water, social security, education and emergency medical treatment. These challenges are caused by resource scarcity and competing priorities in the usage of limited funds, such as debt repayment. Moreover, the government interventions are sometimes not as effective. For instance, giving of relief food and water in the Nairobi slums affected by floods is only a temporary redress mechanism which fails to address the systemic causes of this problem, which include adverse climate change effects, poor drainage system, over-crowding, improper land zoning and inadequate empowerment opportunities.

SIBs offer a viable and alternative solution to these problems. Firstly, to solve the financing gaps, funds can be pooled from different sources such as institutional investors, trusts, NGOs, foundations, charity organisations or crowdfunding. The SIB intermediary would work together with the service providers to ensure that the social intervention is achieved, such as training and job placement, to address the unemployment problem, as was the case in South Africa. They would also ensure that the project meets the outcome metrics upon evaluation so that the government, which is the outcome funder, would pay out the investors the initial capital and interest as agreed. The key component associated with SIBs is the fact that payment is only made after the outcome is met, which would solve the challenge of stalling and incompletion of government projects despite the allocation of funds. The challenge associated with payment upon the SIB’s success is that the Kenyan government has a history of accruing many pending bills, which reduces investors' confidence and therefore, the process must be transparent if SIBs are to work effectively.

Secondly, specialist service providers catalyse the achievement of the social intervention. For instance, in the South African Workforce SIB, the service providers specialised in training and job placements who understood the root of the problem and how to solve it. Consequently, the redress mechanisms employed were effective, leading to the success of the SIB. The implementation of SIBs in Kenya can be quite effective in solving social problems since the service providers must be experts, given that the returns are pegged on results. The SIB intermediary structures the deal in terms of raising capital from the investors, coordinating with the service providers and managing the payout terms, hence minimising the corruption aspect that has ailed government projects for years in the name of bureaucracy. Cronyism witnessed in government tendering is also eliminated.

Thirdly, SIBs are privately funded and time-bound, giving the projects’ implementation an incentive to be done right and within the set span. As such, SIB intermediaries must ensure that the capital raised is used in a proper and accountable manner to ensure that the social intervention is reached and to ensure transparency to the investors. This act is in line with Cohen’s proposition of ‘No impact, No deal’. As such, the best service providers must put their best foot forward to deliver results in line with the outcome metrics for the benefit of society and investors, consequently leaving zero room for stalling and mediocrity in projects.

In conclusion, Kenya has great potential to become a developed country. The advancements in technology, its strategic location, the nature and scenery and a skilful labour force are just some of Kenya’s strengths that would catalyse this achievement. However, the myriad of social challenges facing the population reduces the people’s capacity to achieve their full potential, which in turn derails socio-economic development. Social Impact Bonds offer an alternative means of raising capital for different projects, and the pay-for-success aspect ensures better implementation of these projects compared to the traditional way of the government allocating the requisite funds and implementing policies, which takes too much time because of corruption. As such, the government, legislature, investors, service providers and the public should embrace this concept as a means of engineering socio-economic development in the country.