Tuesday, August 19, 2025

Author: Feswal Abdallah

Category: Education

⏱️ Estimated Read Time: 10 min read

Education is globally recognised as a driver of productivity and long-term growth, with Total Factor Productivity (TFP) data consistently linking human capital development to economic advancement. Education has consistently contributed to improvements in total factor productivity globally. In the US boom years, education contributed about 14% of an increment in TFP, as corroborated by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee in their research in 2019. Similarly, Jung Woo Jin found that a 1% increase in lower secondary completion rates boosts TFP by 0.07, underscoring the productivity gains tied to educational attainment. Governments leverage fiscal policy to shape educational outcomes, aiming to enhance access, equity, and quality. In Kenya, education levels have steadily improved, yet disparities in quality remain stark—especially across rural and marginalised communities. Education sector allocation has increased by over Ksh 200 billion in the last six years, has the highest share of the total national budget, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Education Sector Allocation in Kenya (FY 2020/21–2025/26).

| Fiscal Year | Education Allocation (Ksh Billion) | % Share of Total National Budget |

| 2020/21 | 497.7 | 25.9% |

| 2021/22 | 539.9 | 26.7% |

| 2022/23 | 544.4 | 26.4% |

| 2023/24 | 628.6 | 27.4% |

| 2024/25 | 656.6 | 27.6% |

| 2025/26 | 702.7 | 28.0% |

Source: Authors’ Compilation from National Treasury Data, Kenya.

Table 1 shows a steady increase in Kenya’s education sector allocation from KSh 497.7 billion in FY 2020/21 to KSh 702.7 billion in FY 2025/26 in nominal terms, with the share of the national budget rising from 25.9% to 28.0% over the same period. This upward trend reflects the government's growing commitment to investing in human capital and expanding access to education.

Yet despite Kenya’s substantial fiscal commitment to the education sector, learning outcomes, infrastructure distribution, and overall education quality remain uneven across the country. The challenge lies not in the volume of the allocation, but in how efficiently it is spent and how well it aligns with the targets of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4)—particularly those focused on equity, quality, and measurable learning outcomes. According to the KNBS Economic Survey 2025 , the Ministry of Education’s expenditure data reveals that the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) consistently receives the largest portion of the education budget, with 55%–60% allocated primarily to teacher salaries, allowances, and pensions. In contrast, the development share, which funds the construction of classrooms, laboratories, dormitories, and sanitation facilities, typically receives only 10%–15% of the total budget.

This allocation—where most of the funding goes to recurrent costs, while critical infrastructure and learning support remain underfunded—significantly undermines efforts to improve education quality. The increment in education funding over time is exaggerated by the recurrent expenditure share, hence does not reflect the improvements in the development of education-supporting infrastructure. Consequently, many learners continue to study in overcrowded, poorly equipped, and unequal environments.

Fiscal Policy, government expenditure and revenue collection, can enhance long-term economic growth by increasing investment in human capital and infrastructure, including schools and teacher training and retraining. By adjusting allocation levels, governments can achieve such desired policy objectives as increased growth and employment, macroeconomic stability, income distribution, allocative efficiency and operational efficiency

Kenya’s education system has made bold strides in expanding access, with initiatives like the 100% transition policy driving significant growth in student enrollment across secondary schools, TVETs, and universities. In 2024 alone, over 962,000 students sat for the High school final examination; however, only a fifth, 201,146, qualified for university, and just 153,274 were placed in degree programmes. While 476,889 students joined TVET and diploma courses, many others either dropped out or entered the labour sector, especially the informal sector. This was an improvement from 2023 enrollment as of the KUCCPS placement database, where about 289, 560 students only managed to join TVETs and enrolled for diploma courses, while 140,107 students were placed in degree programmes out of 173,244 who qualified for degree programmes. These figures reflect improved access—but also expose the persistent barriers of poverty and inequality, as highlighted by Afroza in the Afrobarometer report, which continue to limit opportunities for many learners in developing countries. Enrollment over the years has seen increasing numbers, as evident in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Kenya’s School Enrolment from 2020 – 2024

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Pre-primary Schools | 2,832,897 | 2,845,265 | 2,829,972 | 2,885,636 | 2,914,492* | |

| Primary and Junior School | 10,170.1 | 10,285.1 | 10,364.2 | 10,397.1 | 10,733.3* | |

| Secondary Schools | 3,520.4 | 3,692.0 | 3,920.3 | 4,109.5 | 4,321.6* | |

| TVET Institutions | 451,205 | 503,798 | 562,499 | 642,726 | 709,885* | |

| University Enrolment | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25* | ||

| 562,066 | 562,925 | 579,046 | 631,307 | |||

| University Enrolment of Diploma and Certificate Courses Students |

63,957 |

71,472 |

79,792 |

57,367 | ||

Source: Authors’ Compilation from KNBS - Economic Survey 2025.

Table 2 reveals a consistent rise in student enrolment across all levels of education in Kenya from 2020 to 2024, especially in secondary schools, TVET institutions, and universities. This growth signals expanding access and demand for education, which is a positive step toward inclusivity and human capital development. Table 3 highlights key trends in teacher and trainer enrollment across Kenya’s education system from 2020 to 2024, revealing both progress and areas of concern about education quality.

Table 3: Teachers and Trainers Enrolment 2020 – 2024

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024* | |

| Pre-primary Schools | 95,241 | 68,599 | 78,333 | 75,383 | 77,583 |

| Public Primary and Junior School | 218,077 | 222,443 | 221,510 | 219,727 | 212,602 |

| Secondary Schools & Teacher Training Colleges | 113,144 | 120,265 | 124,992 | 125,563 | 130,818 |

| TVET Institutions Trainers | - | 16,358 | 19,921 | 23,882 | 34,811 |

Source: Authors’ Compilation from KNBS - Economic Survey 2025.

Table 2 and Table 3 show progress in demand for training for secondary and TVET trainers, an indicator of the growing supply of teaching staff in these areas. Contrary to high learning areas, the decline in primary-level teachers and shrinking demand for training in pre-primary teaching categories raise concerns about the foundational learning teaching staff supply.

The reality painted by Tables 2 and 3 above makes it evident that Kenya's education sector has experienced a consistent rise in student enrollment across all levels from 2020 to 2024, while teacher and trainer numbers have either stagnated or grown at a much slower pace. This imbalance has led to an increasingly unfavourable student-teacher ratio, which directly impacts the quality of education delivery.

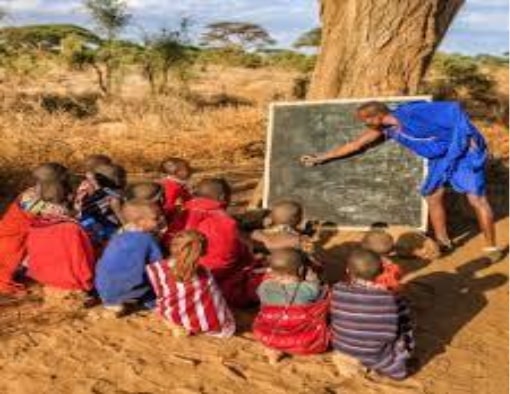

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) recommends a teacher-student ratio of 25 students per teacher for primary schools. This ratio is based on research that shows that students with smaller class sizes tend to perform better academically. Kenya's current recommended teacher-student ratio is 40 students per teacher. However, some parts of the country have a teacher-student ratio of 70:1. This is significantly higher than the UNESCO-recommended ratio, and it is one of the highest teacher-student ratios in the world. Such conditions make it difficult for teachers to deliver personalised instruction, manage classrooms effectively, and track student progress—undermining the very essence of quality education. Without targeted fiscal policies to recruit, train, and retain more teachers, increased funding alone cannot guarantee improved learning outcomes. Barrett further argues that quality is value-laden and must be contextualised within local cultural and developmental goals.

An illustration of Fiscal policy interaction with Education.

Source: Author’s Design

While Kenya has made notable progress in increasing education funding, a significant gap remains between expanding access and ensuring quality learning. According to UNESCO, only 60% of adolescents globally meet basic literacy and numeracy standards, and the situation is more severe in developing countries.

In Kenya, a World Bank Report reveal that nearly 75% of Grade 3 learners struggle with basic reading tasks—such as reading simple sentences, highlighting a disconnect between enrollment and actual learning. These figures suggest that while more children are in school, many are not acquiring the foundational skills essential for academic progression and lifelong success. It is important to consider that simply increasing the budget allocation may not guarantee success. The Ministry of Education should identify areas of inefficiency, reduce wastage, and improve financial management practices. By ensuring that the available resources are effectively utilised, the sector can maximise the impact of its budget and deliver quality education through available infrastructures, recommended student-to-teacher ratio and a well-structured education system for all.

The education sector ought to achieve its target without compromising the quality of education. In 2025, the government initially planned to construct 16,000 classrooms, but this was later revised to 18,000, with some sources stating 7,200 are being added specifically in the first half of 2025. When targets are met consistently, stakeholders, including parents, teachers, and policymakers, are more likely to support further investments in education.

It is important to note that revising targets should not imply accepting low standards or compromising the quality of education. Expanding classroom infrastructure without ensuring equitable teacher distribution across regions risks undermining the very goal of quality education, as physical access alone cannot substitute for effective instruction.

Despite Kenya’s record-high education allocations, as shown in Table 1, the reality reveals persistent gaps in quality. Overcrowded classrooms, teacher shortages, and uneven infrastructure highlight that the issue isn’t just how much is spent—but how effectively it’s used and whether it reaches those most in need. To truly transform education, fiscal policy must confront systemic inefficiencies and prioritise equity, accountability, and measurable outcomes. Urban schools often get more resources, including teaching staff and modern facilities. In contrast, rural and ASAL areas lag, lacking even basic infrastructure. The audit, sanctioned by the National Assembly Public Accounts Committee (PAC), covering the financial years 2020/2021 to 2023/2024, showed 354 public secondary schools, 99 JSS, and 270 public primary schools were overfunded by Sh3.7 billion, while 334 public secondary schools, 244 JSS, and 230 primary schools were underfunded by Sh2.14 billion. The audit showed that out of 83 schools sampled, 14 non-existent schools received Sh16.6B, 6 closed ones got Sh889K, and 13 mismatched entries received Sh11M—revealing critical gaps in accountability.

To close the gap between access and quality in our education system, moving forward, fiscal policy must go beyond funding and focus on strategic implementation. This includes recruiting and equitably deploying qualified teachers, linking budgets to measurable outcomes, and investing in infrastructure where it’s needed most. Strengthening monitoring systems, expanding support for TVET, and involving communities in decision-making are also vital. Only through targeted, accountable, and inclusive spending can Kenya’s education sector deliver quality learning for all, not just education for all.

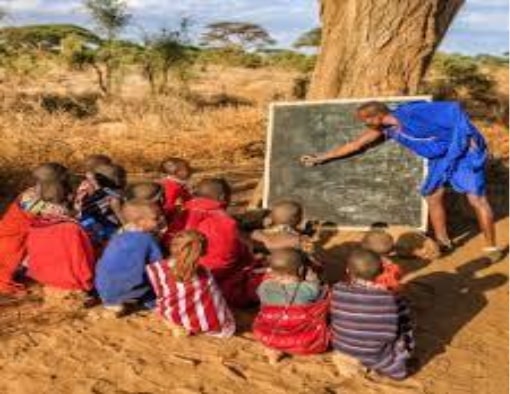

In conclusion, while it is true that Kenya’s rising education budget reflects a commendable commitment to human capital development and national progress. It is equally important that, as the data and lived realities show, access alone does not guarantee quality, and a huge share of the budget is recurrent expenditure. Overcrowded classrooms, uneven teacher distribution, and under-resourced schools continue to hinder learning outcomes, especially in marginalised regions. Without targeted fiscal strategies that prioritise equity, efficiency, and measurable impact, the promise of quality education will remain out of reach for many learners in many classrooms, with some learning under the trees in marginalised areas.

To truly fund the future, Kenya must move beyond impressive budget figures and confront the systemic challenges that dilute their effectiveness. This means sealing cracks in accountability, ensuring resources reach those most in need, and aligning spending with SDG 4 goals. Every shilling must be more than a number—it must be a step toward meaningful learning, opportunity, and transformation for every child, in every classroom, for quality education for all to be attained.