Monday, October 20, 2025

Author: Alex Maina

Category: Women, Economic Growth, Inclusivity

⏱️ Estimated Read Time: 5 min read

Elevating women’s productivity is one of the most underleveraged economic strategies in Kenya’s development agenda. While women constitute nearly half of the labour force, structural inefficiencies continue to suppress the full realisation of their economic potential. Closing the productivity gap is not just a matter of fairness; it is a strategic imperative for national competitiveness, innovation, and sustainable growth. Every hour of unpaid or underpaid work, every skill unutilised, and every barrier unaddressed translates into lost productivity, hence lost GDP.

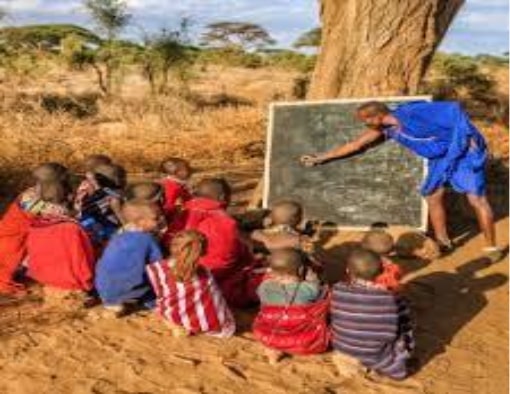

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) Women and Men in Kenya 2022 report (p. 57), 26.1% of women in agriculture have no formal education compared to 21.3% of men, as illustrated in Figure 1. Only 0.1% of women have received formal training in agriculture, while 0.4% of men face a critical constraint on both productivity and technological adoption. Even at higher educational levels, only 5.3% of women in agriculture have completed tertiary education, against 7.8% of men, as indicated in Figures 1 and 2. These disparities directly hinder rural productivity, limit innovation, and stall national food security outcomes.

Figure 1: Population in Agriculture based on Level of Education

Source: KNBS 2022 on Gender facts and figures

Figure 2: Gender based distribution in the Agriculture Sector

Source: KNBS 2022 on Gender facts and figures

Education remains the cornerstone of human capital development; in an article by Amavilah, Voxi Heinrich (2014) on the Lucas and Romer Production functions stated that knowledge equals technology and human capital. Hence, a country should invest more in education, research and innovation, whose spillover has a huge positive externality. But in Kenya today, dropout rates remain a significant challenge. The school dropout rate peaks at age 15 for girls, reaching nearly 9% (KNBS 2022, p. 33), as illustrated in Figure 3. Contributing factors include poverty, early marriage, household responsibilities, and inadequate sanitation facilities. The gender parity index at the secondary school level remains below 1 in favour of men, particularly in rural counties, reflecting a system that structurally favours male learners.

Figure 3: School Dropout Rate

Source: Gender facts and figures, KNBS, 2022 Report.

Beyond education, the productivity divide is intensified by the burden of unpaid care work and underpayment. Women in Kenya spend significantly more time on household and caregiving duties than men, which limits their participation in paid labour and entrepreneurial ventures. Women spend about twice time in caregiving as men. Research conducted by the Kenya Revenue Authority (2020) on determinants of the gender wage gap in Bungoma County noted that women earn KSh 68 for every KSh 100 earned by men for doing a similar job, as shown in Table 1 below. The underpayment reduces their morale at work, hence reducing productivity. A productive human capital means not only economic growth, but also economic development- improving people’s welfare, and hence increased GDP.

Table 1: Determinants of Gender Wage Gap in Bungoma County

Source: Kenya Revenue Authority, 2020

Additionally, women-owned establishments tend to have lower productivity than those owned by men. This productivity gap between the two genders is largely attributed to factors such as firm size, level of education, number of working hours, startup capital, and the use of technology, as well as other barriers; this gap is also more prevalent in informal sector firms. These barriers hinder women-owned establishments from embracing productivity and, hence, limit economic growth. As noted by UN Women (2022), the poverty experienced by women is a major drag on national productivity, particularly in economies with large informal sectors and weak social support systems.

Women dominate the informal sector, hence are largely disconnected from regulatory and support frameworks. The KNBS 2022 data (p. 44) shows that 43% of employed women are contributing family workers or own-account workers, compared to only 28% of men. Conversely, only 27% of women hold paid positions in contrast to 43% of men; an employment quality gap that directly undermines output and resilience.

To drive productivity gains, women must be integrated into high-potential, value-adding sectors through targeted technical training, financial support, encouraged technology adoption, and infrastructure investment. For example, integrating mechanisation and digital tools into women-led Agri-enterprises could significantly raise output levels. According to the World Bank (2022, Jobs Diagnostic Kenya, p. 21), women are disproportionately clustered in low-productivity and informal sectors, while formal manufacturing and service industries remain male-dominated, as indicated in Figure 4. This inequality of labour reduces the economy’s overall efficiency.

Figure 4: Earnings by Gender

Source: World Bank: Opportunities for making growth more inclusive during challenging times.

The national development strategy must embed gender-sensitive frameworks into all pillars: education, agriculture, infrastructure, finance, and trade. This includes expanding childcare infrastructure, launching gender-focused industrial parks, and scaling up affirmative procurement policies. Productivity is not simply an outcome of effort; it is a function of opportunity, environment, and policy coherence.

Increasing women’s productivity in Kenya could raise GDP by up to 23% especially in manufacturing, which is a sector of agricultural value addition, according to global gender growth modelling. A country that sidelines half its population cannot claim to pursue inclusive development. Kenya’s next economic breakthrough may not rest solely on resources or aid but will be significantly propelled by unlocking the full productive power of its women.